A Blog about Access to Safe Drinking Water

Drinking “Wicked” Water

Next to air, water is the most important resource on Earth (Earthwatch, 2018). Every life form, every species needs it to survive. Yet a third of people in this world are faced with lack of access to safe freshwater, and 60% lack access to sanitation (WHO, 2017). The issue of freshwater access is reaching crisis proportions and yet many remain blissfully ignorant or deny the problem outright (Sherriff, N., 2016). We will explore the water crisis worldwide, and then show how we have degraded and polluted waters here at home, in an attempt to convince you that our situation needs to be addressed now. We will discuss the concept of a “tipping point” and how close we might be to such a thing. We will ask questions that you, the reader, must answer for yourself, for the desperately needed changes will only come when enough people make up their minds to believe and take action.

Would you drink this water?

Of course not…

Chances are, if you’re reading this, you’re not faced with that situation. Chances are, you’re from a first world country, where water flows from a tap, the water supply is “protected,” and fossil fuels drive your economy. Chances are, in your mind, the concept of a water crisis is somehow tied to the above picture: an unfortunate situation on the other side of the world, and therefore not related to you. For generations, this was a worldview we could apparently afford to hold.

No longer.

The Situation Worldwide

In 2010, the UN General Assembly explicitly recognized the human right to water and sanitation. (UN, 2010). Everyone has the right to “sufficient, continuous, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic use” (UN International Decade for Action). The UN has also stated that “the human right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity. It is a prerequisite for the realization of other human rights.” (UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESC), 2003, par. 1). Yet, water scarcity continues to exist, and the problem is escalating worldwide. (Ibid)

Living in a First World nation like Canada, it may be easier to ignore the water crisis, and pretend that it’s not going to affect us. But the crisis is global, and it will affect us all one way or another, unless we find and implement solutions. What we face, not just in the terms of water issues, but with the sustainability crisis in this world in general, is a “wicked” problem (Curran, D., 2009). A wicked problem doesn’t necessarily imply that it is a problem based in evil, but rather that it is extremely complex, and “highly resistant to a solution.” (Australian Public Service Commission, 2019, par. 1). To find a solution, we must first define the problem, and wicked problems are notoriously hard to define. (ac4d). But even before we can define it, we must understand and believe that there is a problem.

We must wake up and realize that the entire world is in a sustainability crisis of unprecedented proportions. Across the world, countries and cities have declared a State of Environmental and Climate Emergency, affecting some 49 million people, including the home city of the authors of this blog, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (Craggs, S., 2019).

We’re Ignoring the Plight of the Poor

The reality is already stark for many. The many, unfortunately, are the poorest. When you consider that “access to freshwater” doesn’t necessarily mean water flowing from a tap, but rather safe water within a reasonable distance (UN International Decade for Action), this means there really is no water nearby for those who are without access, and/or that the water that is around is unsafe to drink..

Some suffer alone…

Water scarcity, droughts and water-driven socio-political conflicts have resulted in the displacement of millions of people worldwide (Sentlinger, K., 2019). People cannot survive without water, so when the water goes away, becomes unsafe to drink or use, or when conflicts over water escalate, people have to leave their homes. This is already happening to millions of people around the globe.

Affected people are protesting…

Others just die…

“Every two minutes, a child dies from a water related disease.”

Water.Org, 2019

If it’s not happening to us, why should we care? The problem is, it’s happening in developing – let’s just call a spade a spade, and say it – poor countries. Why do we do nothing in the face of this calamity? Is there a possibility that one day, sooner than we think, the crisis might come to us too?

We’re Addicted to Oil…

A recent study, from which the following tables were obtained (Spang, E. S., et al, 2014) estimates that we use 52 billion gallons of freshwater per year globally, to produce energy. The graph below shows how much water we use for each kind of energy and fuel production. We ask you to note the disproportionate amount used in the oil industry versus the rest of the industries, as well as the disproportionate use of resources in affluent versus poor countries. We ask: how much could we reduce our impact if we changed our focus away from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy? And what kind of a difference would equality make?

Note how much of our freshwater is being used for energy production. Note the ones that use the most, versus the ones that use the least.

The map above shows water consumption for energy production by country. The darker the color of the country, the more water they use for energy production. The darker the color of the country, the more water they use for energy production. Which countries are using the most? Rich countries or poor countries?

Who, in the graph above, is using the most water for energy consumption? How disproportionate is that usage to the rest of the world?

We are changing the geography of the Earth

If the plight of people across the world from us, or how much water we use and contaminate for the purposes of energy are not enough to convince us that there is a water crisis, let us consider how, due to human caused climate change, and human interventions such as overuse, damming, and man caused climate change, we are changing the geography of the planet. Our increasing population and our consumption driven lifestyles have caused freshwater use to have increased nearly six-fold since 1900 (Ritchie, H., 2015). National Geographic recently published an article outlining how 8 major worldwide rivers have run dry. (Howard, B., & Borunda, A., 2019). These include the Colorado (US), the Indus (Pakistan), the Amu Darya and Syr Darya (two rivers connected to the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan), the Rio Grande (US), the Yellow River (China), the Teesta (India) , and the Murray River (Australia). These rivers have dried up as a result of man-made causes like irrigation, diversion and disruption, as well as from climate change (Ibid), which is also man-caused. It bears repeating: major, iconic rivers are running dry worldwide. Which will be the next major river to dry up?

The Political Side of the Story

In the face of our looming global emergency, the UN has established 17 goals that pertain to creating a sustainable future for the planet.(UN, 2019). Ensuring access to water and sanitation for all is goal number six (UN, 2019). Does this mean that water and access to safe drinking water and sanitation is the sixth most important problem in the world? No. What it means is that lack of access to water and sanitation is one of many interconnected problems – including poverty – that interact with each other and make wicked problem hard to define clearly, let alone solve. (A wicked problem has many interrelated causes and effects.)

We are running out of resources fast, and in the midst of a climate change event. Overpopulation, pollution, and unsustainable water use are threatening our water supply globally (WWF, 2019). All these issues are interconnected. There are many ways in which humanity might suffer en masse if our crisis is not addressed in time (IPCC, 2018), but running out of freshwater is going to compound the problem exponentially (Global Environment Facility, 2015). And yet, we remain in denial, and use water as if it is an unending resource. Perhaps the most overlooked, yet most significant symbol of the First World’s disregard for water is what has been referred to as “America’s largest crop” (Sherriff, N., 2016), our lawns. While children die from water borne diseases, and their mothers walk mile upon mile day after day to get contaminated water from an uncertain source, we shower 60 000 square miles worth of lawns in the US alone with endless amounts of water every day. (Ibid) Why? To show that we are better than others? How is this sustainable? How is this water use justifiable?

Water is being misused and degraded at a rate which has led the UN to warn that the world will run out of water – i.e., about 5 billion people will not have access to safe water – by 2050 (Watts, 2018). This should scare us, but somehow it doesn’t seem to. The problem is that we, in the First World, do not see ourselves as part of that scenario. We feel exempt, entitled. We can hit the snooze button on the emergency and declare to ourselves “it will happen to someone else, not me. I won’t be part of that affected population because I live in an affluent area that has abundant freshwater.” But what if it is happening to us right now and we just haven’t woken up to it yet? (Do you know what is in the water you drink? Read on to find out.)

The state of water in Canada

Canada’s population makes up about one half of a percent of the world’s population. We have, available to us, 7% of the world’s renewable freshwater (Government of Canada). This should be enough. But apparently, it isn’t.

An article in the online resource The Conversation (Pomeroy, 2019) put it very clearly: “Canadians can no longer be assured that our waters are abundant, safe and secure. As global temperatures continue to increase, our glaciers melt, permafrost thaws, river flows become unpredictable and lakes warm and fill with toxic algae.” (There is always more than one explanation for a wicked problem)

Another recent article in MacLeans (Quigley, 2018) concurs that our freshwater systems “are under strain from threats of aging infrastructure, climate change causing floods and droughts, cyberattacks, transboundary conflicts with the U.S., contamination due to hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and the sale of water to foreign markets.” (Every wicked problem is a symptom of another problem.)

How about this water? Would you drink this water? It’s “first world” water after all…

Our search for energy doesn’t just use water: It contaminates water

Would you be surprised to find out that this water is an example of water contaminated by “fracking,” a mining process used for extracting oil or natural gas from the ground? You might indeed be surprised to find this out, because although there have been many cases where fracking has contaminated community drinking water supplies (Niforak, A., 2016), oil companies place gag orders on those affected, preventing them from speaking to the media on the subject. (Frack Free Nottinghamshire, 2014). Surely, though, this doesn’t affect you personally, right?

Would you be concerned if you saw this map showing fracking activity in relation to major water aquifers in Canada?

Source: Alternatives Journal (AJ Staff) 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.alternativesjournal.ca/energy-and-resources/fracking-hotspots

How close to one of those hotspots do you live?

How would you feel if you saw this map depicting the state of groundwater in Canada?

The map above is one of several that were issued in a 2017 WWF (World Wildlife Foundation) report on Canada’s Freshwater. When WWF conducted their assessment on the health of our waters, the first problem they found was that despite widespread assumptions about Canada’s water being pristine, there was such a lack of data about our water supply, that it was a serious obstacle to understanding the health of our freshwater ecosystems (WWF Canada, 2017). However, even under the data-deficient conditions they faced, they found “significant evidence of disruption, whether from pipeline incidents, oil and gas development, hydropower dams, agricultural runoff, pulp and paper processing, fragmentation, urbanization or other activities”(Ibid, p. 3), which resulted in a series of maps like the one above, showing graphically how our freshwater supply is in jeopardy. In other words, we are not as well-placed with respect to water as we should be, given the abundance of natural freshwater supplies we enjoy. How, when we have one of the most abundant freshwater systems on the planet, did we manage to degrade our freshwater sources so quickly and thoroughly?

Click here to take a look at all the maps from the WWF study.

Access to water in Canada

Would you be surprised to learn that many Indigenous communities in Canada are and have been under long term boil water advisories? (Nadeem, S., et al, 2018) A boil water advisory is issued when the water is unsafe to drink, usually due to elevated germ contamination, and long term means more than one year (Alberta Health Services, 2018). This is not surprising when you consider how we have treated our indigenous peoples in the past, but the boil advisories are affecting more and more communities – including large cities like Montreal (CBC News, 2019), Hamilton (City of Hamilton, 2018) and the Greater Toronto area (Newstalk 1010, 2018).

Meanwhile, a recent investigational study found that 33% of lead tests in Canada’s drinking water, in several major cities, contained high amounts of lead. (Global News/The Toronto Sun, 2019). Just because water comes out of a tap, doesn’t mean it is safe to drink, as it turns out.

This map shows the current boil advisories in effect in Canada as of the date of this paper.

These numbers change often: to find the current map, please visit: https://www.watertoday.ca/

What about this water?

Information extracted from IPTC Photo Metadata

Surely this is the water that we all want to drink: clear and limpid, in a clean glass, free flowing from a nearby tap…But where does this water come from, in this polluted, industrialized world? We may pity those who have to gather around a muddy waterhole in the third world, but what’s in our first world water?

Pollution

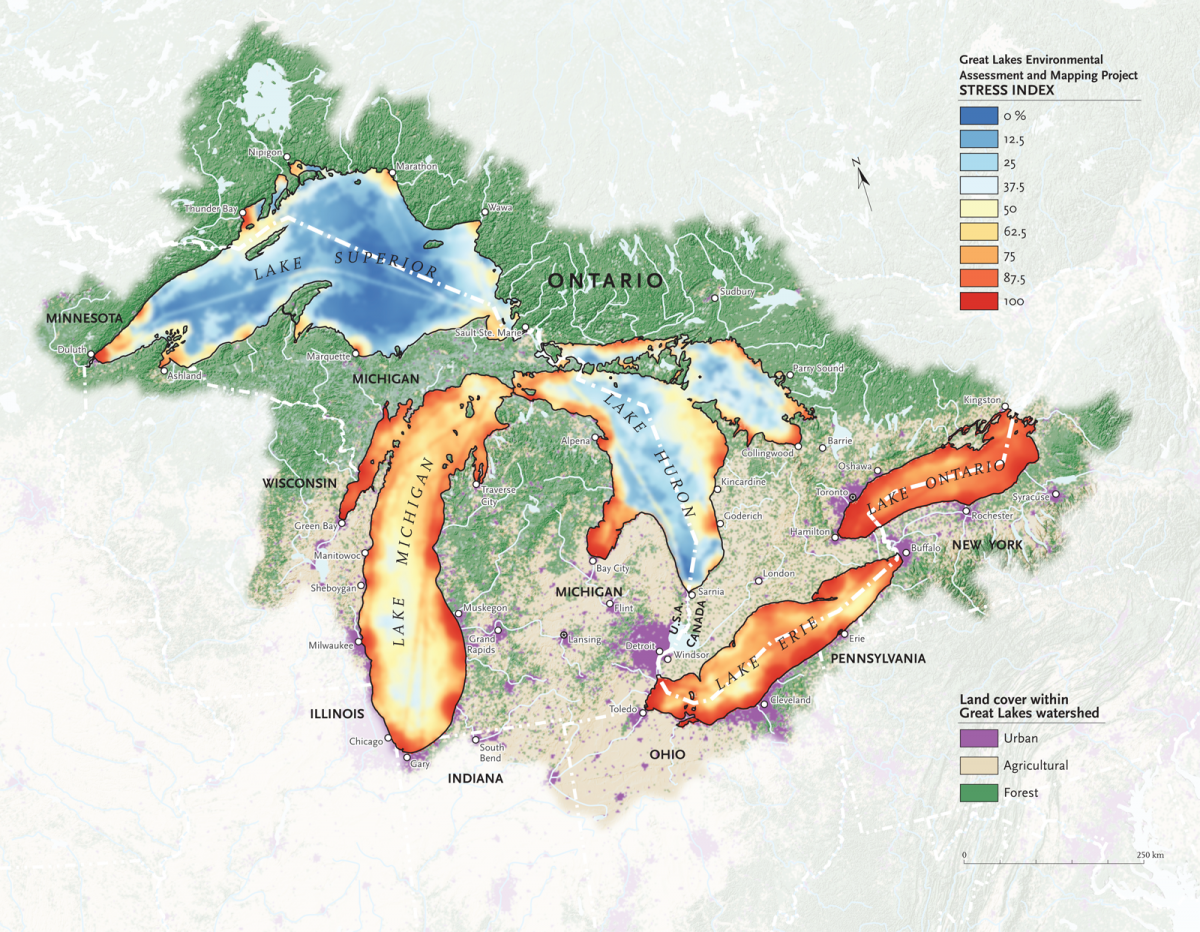

If you’re of the 25% of Canadians or 10% of Americans whose drinking water comes from the Great Lakes, the world’s largest freshwater system, containing 20% of the world’s surface freshwater ( Zimmerman, K., 2017), and you think this gives you access to safe drinking water, think again. This map, issued by Canadian Geographic, shows the levels of stress in the Great Lakes, as of 2013 – (eight years of mistreatment ago.)

The Great Lakes Environmental Assessment and Mapping Project — a group of about 20 American and Canadian researchers and environmentalists — produced the data for the map above, which illustrates the cumulative impacts of human activity across the Great Lakes. (Walker, N., 2017). So what have we done to our Great Lakes?

Pharmaceuticals and Sewage

Studies have found pharmaceuticals such as acetaminophen, codeine, antibiotics, hormones, steroids, and anti-epileptic compounds, and dozens of other pharmaceuticals in the Great Lakes “at levels high enough to be “of environmental concern” (Crowe, K., 2017, par 6),” and in levels high enough to cause the development of what is called “intersex fish”, wherein the male fish developed eggs in their testes (Ibid, par. 12).

A study conducted by Pollution Probe and the clean water foundation and submitted to environment and climate change Canada found that Hamilton Harbour is the most contaminated study area in the Great Lakes basin.(Pollution Probe &Clean Water Foundation, 2019).

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/insight/2011/07/08/lake_of_shame_ontarios_pollution_problem/fealakeopollution.jpeg)

Pollution dumped into that area includes discharge from the Woodward Avenue Wastewater Treatment Plant (McNeil, M., 2011). Not far away, Toronto’s gigantic sewer system overflows when it rains hard, from 50 to 60 times per year. (Zerbisias, A., 2011) Sewage treatment plants are not currently designed to remove pharmaceuticals from water, nor are the facilities that treat water to make it drinkable, though some pharmaceuticals do get removed by some processes (Harvard Health Publishing, 2011). And out of the chemicals that get removed, they create more sludge which is used as fertilizers and getting into the environment another way.(Ibid)

Tipping Points

As a final point, we urge you to consider what would happen if our water system was to hit a tipping point. A tipping point is defined by Merriam Webster as “the critical point in a situation, process, or system beyond which a significant and often unstoppable effect or change takes place.” In terms of water for example, a tipping point is illustrated below, in this map, which shows the state of the major aquifers in the world and their various states of depletion (Buis, A., & Wilson, J., 2017). Those at or near the red end of the scale have already passed their tipping points, the point at which nothing can be done to restore them, and the results from their depletion could be catastrophic.

So what does a catastrophic consequence look like? In 2018, Cape Town, South Africa, a city of 4 million people, came within three months of completely running out of municipal water. (Alexander, C., 2019). This, once again, bears repeating: a major world city was 90 days away from having no more tap water flowing when its residents turned on the taps. The day that the city was due to run out of water, April 12, 2018, was named “Day Zero.” (Ibid, par. 1) The city implemented emergency measures and managed to stave off the disaster until after the next rainy season, but one year later, they continue to operate at about 50% of their capacity. (Ibid, par. 13). What would you do if you turned on the taps and no water came out?

As Anders Berntell, Executive Director Stockholm International Water Institute, stated in his introduction to the December 2009 issue of the Stockholm Water Conference:

“We cannot accurately assess when the “tipping point” for large-scale environmental change will be crossed, but we do know that the changes can come abruptly if they are. As water withdrawals are predicted to increase by 50 percent by 2025 in developing countries, and 18 percent in developed countries, we may be heading into dangerous territory.”

Retrieved from https://www.siwi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/WF-3-4-2009.pdf . Page 2.

Essentially, the point we are trying to make is this: it may not “look” like an emergency to us right now, but we are steadily moving past many “points of no return” with respect to our water resources. When enough tipping points are reached, the crisis will escalate. How long before we realize that we are faced with an emergency of apocalyptic proportions?

Conclusion

So let’s wash our cars and water our lawns. Let’s keep allowing industry to pollute and divert our water. Let’s keep dumping plastic and other garbage into our water, and pretend that it won’t hurt. Let’s pretend that water is an unending resource and will never run out. Then, let’s drink a big tall glass of our own filth – while we can still afford the luxury of ignorance. Because water is set to become more expensive than oil (Ward, A., 2017), and the Big Water companies are watching and not waiting to take over the water supply (Yang, J., 2019). When we have destroyed our drinking water supply and exacerbated climate change in the process, and we hit “Day Zero” maybe then we will realize that we are also affected by this sustainability emergency. But how many years will we have wasted in the process, and how much worse will our situation be then?

Water is an irreplaceable resource, and we have already degraded and contaminated it to the point where we have created a water crisis. It is our responsibility to clean it up and manage it better, or we may not doom future generations to catastrophe: we may doom ourselves, and soon.

***

We, the authors of this blog post, ask you, our reader, to do the following: ask yourself what water means to you, educate yourself, and take action today to save the water, and save us all.

We can’t drink oil, or the money we make from it.

Please, start a conversation with your loved ones.

Links to action oriented water resources

https://friendsoftheearth.uk/natural-resources/13-best-ways-save-water-stop-climate-breakdown

https://davidsuzuki.org/take-action/

References

Ac4d (n.d.) Wicked problems: Problems Worth Solving. Retrieved from: https://www.wickedproblems.com/1_wicked_problems.php

Alberta Health Services. (2018). How to Use Water Safely During a Boil Water Advisory. Alberta Health Services, Safe Healthy Environments. Retrieved from https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/wf/eph/wf-eph-boil-water-advisory-water-home-safety.pdf

Alexander, C., (2019). Cape Town’s ‘Day Zero’ water crisis, one year later. CITYLAB. Retrieved from https://www.citylab.com/environment/2019/04/cape-town-water-conservation-south-africa-drought/587011/

Alternatives Journal. AJ Staff (2014). Map of Canadian Fracking Hotspots and accompanying comments obtained from: Fracking Hotspots in Canada. Alternatives Journal. Retrieved from https://www.alternativesjournal.ca/energy-and-resources/fracking-hotspots

Australian Public Service Commission. (2019). Tackling wicked problems: A public policy perspective. Retrieved from: https://www.apsc.gov.au/tackling-wicked-problems-public-policy-perspective

Berntall, A., (2009). PUSHING THE LIMITS. Stockholm Water Front: A forum for global water issues. (No. 3-4, December 2009). [Report]. Retrieved from https://www.siwi.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/WF-3-4-2009.pdf

Buis, A., & Wilson, J. (2017) Trends in Groundwater Storage from NASA GRACE Mission (2003-2013). From: Study: Third of Big Groundwater Basins in Distress. NASA. Retrieved from https://www.nasa.gov/jpl/grace/study-third-of-big-groundwater-basins-in-distress

CBC News. (2019) Boil Water Advisory Issued in Montreal Borough of Anjou. CBC News. Retrieved From https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/boil-water-anjou-1.5078774

City of Hamilton. (2018) Delbrook Court Precautionary Boil Water Advisory Lifted. City of Hamilton News Releases. Retrieved from https://www.hamilton.ca/government-information/news-centre/news-releases?tag=boil-water-advisory

CNN (2019). Haiti’s Water Crisis. [Video] From Stories Worth Watching. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2014/04/16/spc-vital-signs-clean-water-crisis.cnn

CNN. (2019) A young Haitian Woman struggles with water access daily. [Photograph] CNN (2019). Haiti’s Water Crisis. From Stories Worth Watching . Retrieved from https://cdn.cnn.com/cnnnext/dam/assets/140416140353-spc-vital-signs-clean-water-crisis-00020212-story-top.jpg

Craggs, S. (2019). Hamilton Declares a Climate Change Emergency. CBC News. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hamilton/climate-change-1.5061326

Crowe, K. (2014). Drinking Water Contaminated by Excreted Drugs a Growing Concern. CBC News. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/drinking-water-contaminated-by-excreted-drugs-a-growing-concern-1.2772289

Curran, D., (2009). Wicked. Alternatives Journal, 35(5), 8-11. Retrieved from https://www.alternativesjournal.ca/policy-and-politics/wicked

Earthwatch. (2018). Freshwater watch. Retrieved from https://freshwaterwatch.thewaterhub.org/content/water-precious-resource

Frack Free Nottinghamshire. (2014) Myth #7: Fracking Has Never Contaminated Drinking Water. Retrieved from http://frackfreenotts.org.uk/fracking-myths/myth-7-water/

Frack Free Nottinghamshire. (2014) Photograph of a contaminated mug of water. [Photograph] From Myth #7: Fracking Has Never Contaminated Drinking Water. Retrieved from http://frackfreenotts.org.uk/fracking-myths/myth-7-water/

Global Environment Facility. (2015) The Importance of Water Sustainability. Newsroom Report. Retrieved from http://www.thegef.org/news/importance-water-sustainability

Global News, The Toronto Star, and Institute for Investigative Journalism. (2019). Is Canada’s Tap Water Safe? Thousands of test results show high lead levels across the country. Global News (online). Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/6114854/canada-tapwater-high-lead-levels-investigation/

Government of Canada. (n.d.) Water Frequently Asked Questions: Water Quantity. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/water-overview/frequently-asked-questions.html

Harvard Health Publishing. (2011) Drugs in the Water. Harvard Medical School: Harvard Health Letter. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/drugs-in-the-water

Howard, B., & Borunda, A., (2019) 8 Mighty Rivers Run Dry From Overuse. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/photos/rivers-run-dry/

IPCC. (2018). Special Report Global Warming of 1.5 ⁰C: Summary for Policymakers. IPCC. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/

Jacobo, J. (2019). Women throw earthen pitchers onto the ground in protest against the shortage of drinking water outside the municipal corporation office in Ahmedabad, India, May 16, 2019. [Photograph] From: 17 Countries – Home to 25% of the World’s Population – facing water crises, organization says. ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/International/17-countries-home-25-worlds-population-facing-water/story?id=64827506

Jolly, T. (2014) KwaMthethwa residents collect untreated dam water which they share with cows and goats because of broken water pipes. [Photograph] From “Accusations Fly About Water Supply Issues.” Zululand Observer. Retrieved from https://zululandobserver.co.za/50735/corruption-allegations-around-water-supply/

Knowles-Coursin, M. (UNICEF) (2019). A mother cares for her son who is being treated for cholera at a UNICEF-supported cholera treatment center in Baidoa, Somalia. [Photograph]. From: Dying of thirst: The global water crisis. A GFA Special Report by Holt, P. Retrieved from https://www.gfa.org/special-report/dying-of-thirst-global-water-crisis/

McNeil, M. (2011). No End in Sight For Hamilton Harbour Cleanup. The Spectator. Retrieved from https://www.thespec.com/news-story/7975513-no-end-in-sight-for-hamilton-harbour-cleanup/

Nadeem, S., Pearce, J., Seal, A., Attallah, M., Duggan, A., Gayama, Y., and Kashaf, F. (2018). Finding A Solution To Canada’s Indigenous Water Crisis. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44961490

NewsTalk 1010 (2018) Update: Boil Water Advisory in Milton Lifted. NewsTalk 1010. IHeartRadio. Retrieved from https://www.iheartradio.ca/newstalk-1010/news/update-boil-water-advisory-in-milton-lifted-1.8603799

Nikiforuk, A. (2016). Fracking Contaminates Groundwater: Stanford Study. Resilience. Retrieved from https://www.resilience.org/stories/2016-04-15/fracking-contaminates-groundwater-stanford-study/

Pollution Probe & Clean Water Foundation. (2019). Reducing the Impact of Pharmaceuticals in the Great Lakes: Technical Study”. Prepared for Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved from http://www.pollutionprobe.org/wp-content/uploads/Pollution-Probe-Pharmaceuticals-Great-Lakes-Full-Report.pdf (with permission)

Pomeroy, J., DeBeer, C., Adapa, P., & Merrill, S. (March 2019). How Canada Can Solve Its Emerging Water Crisis. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/how-canada-can-solve-its-emerging-water-crisis-114046

Quigley, K. (2018). The Risks Facing Canadian Water: We Shouldn’t Be Framing A Discussion About Water in Isolation of Consideration Like Infrastructure. MacLeans (Originally Published in The Conversation). Retrieved from https://www.macleans.ca/society/the-risks-facing-canadas-drinking-water/

Ritchie, H., and Roser, M. (2015, Revised 2018). Water Use and Stress. Our World In Data. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/water-use-stress

Sentlinger, K. (2019) Water Scarcity and Internally Displaced Persons. The Water Project. Retrieved from https://thewaterproject.org/water-scarcity/water-scarcity-internally-displaced-persons

Shaikh, A. (2017) The Bad News? The World Will Begin Running Out of Water By 2050. The Good News? It’s Not 2050 Yet. UN Dispatch – United Nations News and Commentary. Retrieved from https://www.undispatch.com/bad-news-world-will-begin-running-water-2050-good-news-not-2050-yet/

Sherriff, N., (2016). Drought? What drought? The perils of Water Denial. Ideas.Ted.Com. Retrieved from https://ideas.ted.com/drought-what-drought-the-perils-of-water-denial/

Spang, E., S., et al. (2014) The Water Consumption of Energy Production: An International Comparison. Environmental Resource Letters. (9, 105002). Retrieved from https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/9/10/105002/pdf (Images: Water Consumption for Energy Production graph, Total Water Consumption for Energy Production (WCEP) 2008, and Total WCEP by Energy Category, 2008. )

The Water Brothers. (2019). Water Organizations. TVO Educational Eco-Series. Retrieved from http://thewaterbrothers.ca/education/water-organizations/

UN (2019). Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). (2003). General Comment No. 15: The Right to Water (Arts. 11 and 12 of the Covenant), 20 January 2003, E/C.12/2002/11. Retrieved from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838d11.html

UN International Decade for Action. (n.d.). The human right to water and sanitation. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/human_right_to_water.shtml

UN. (2019). Goal 6: Ensure Access to Water and Sanitation for All. Sustainable Development Goals. UN. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-and-sanitation/

United Nations. (2010). The Human Right to Water and Sanitation. United Nations General Assembly: Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 28 July 2010. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/64/292

UNWater (2019). Water, Food and Energy: Water Facts. United Nations Webpage. Retrieved from https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/water-food-and-energy/

Walker, N. (2017). “Mapping the Human Impact on the Great Lakes.” Canadian Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/mapping-human-impact-great-lakes (Map of Great Lakes Stress)

Walker, N. (2017). Mapping the Human Impact on the Great Lakes. Canadian Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/mapping-human-impact-great-lakes

Ward, A. (2017). Water set to become more valuable than oil. Financial Times. (online) Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/fa9f125c-0b0d-11e7-ac5a-903b21361b43

Water Today. (2019). Advisories. Retrieved from https://www.watertoday.ca/. Used with verbal permission from the publisher.

Water.Org. (2019) The water crisis. Retrieved from https://water.org/our-impact/water-crisis/

Watts, J., (2018). Water Shortages could affect 5 Billion by 2050 UN report Warns. Retreived from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/mar/19/water-shortages-could-affect-5bn-people-by-2050-un-report-warns

WHO. (2017). News Release. Geneva, 12 July 2017. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/12-07-2017-2-1-billion-people-lack-safe-drinking-water-at-home-more-than-twice-as-many-lack-safe-sanitation

WWF Canada. (2017). A National Assessment of Canada’s Freshwater: Watershed Reports. WWF Canada. Retrieved from http://assets.wwf.ca/downloads/WWF_Watershed_Reports_Summit_FINAL_web.pdf

WWF. (2019). Water Scarcity: Overview. Retrieved from https://www.worldwildlife.org/threats/water-scarcity

Yang, J. (2019) The New “Water Barons”: Wall Street Mega-Banks are Buying Up the World’s Water. Global Research. (online) Retrieved from https://www.globalresearch.ca/the-new-water-barons-wall-street-mega-banks-are-buying-up-the-worlds-water/5383274

Zerbisias, A. (2011) Lake of Shame: Ontario’s Pollution Problem. The Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/news/insight/2011/07/08/lake_of_shame_ontarios_pollution_problem.html

Zimmermann, K. (2017) Great Facts About the Five Great Lakes. Live Science. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/29312-great-lakes.html